My underlying belief pertaining to the stock market is that not only does price fluctuate around value, but that cheap stocks can be identified and price volatility can be captured. Not every time, never with perfect certainty, but consistently enough to make the effort worthwhile. This active approach is particularly suitable for tax advantaged vehicles such as IRAs, where realized gains are not penalized and where you have full control over trading (unlike in a 401k, where your choices will likely be limited to broad based indices or in a taxable account where the government hammers you on short term gains).

Technical analysis, which we’ll discuss in some detail in the coming section, takes a short term view – days, weeks, months. It applies mathematical analysis to recent price trends to determine what a stock’s price is likely to do over this relatively shorter timeframe. If technical analysis determines the price is likely to go up, then that stock is currently cheap. If technical analysis determines the price is likely to go down, then that stock is currently rich. Technical analysis is a helpful tool for both active trading (and for obtaining good entry points for a buy and hold portfolio).

An Analogy

Before continuing further, a simple analogy will help illustrate and solidify the main points of active trading. Imagine we’re going on a long horseback ride. It is long enough that we’ll want fresh horses along the way – rather like the Pony Express. We’ll hop from our first horse as it gets tired, onto a fresh one (and so on and so forth), and in the process not fall off and impede our ride. What does this trip require? It requires a stable of good solid horses, some of them fresh horses, knowledge about when one horse is tired and when another is fresh, and lastly being able to efficiently trade horses in mid-flight. The good solid horses are like good solid stocks, ones that aren’t likely to have stupid managements, make too many mistakes, and which evidence a good growth and volatility record. If they also pay a decent and growing dividend, all the better. Think of a cheap stock from your stable as a good horse that is fresh, and a rich stock as a good horse that’s tired. Distinguishing rich from cheap is where technical analysis enters in. They’re all strong horses / stocks; it’s just a matter of whether the horse/stock is tired or fresh. Now think of hopping from one horse to another as selling one stock, that has become rich, to rapidly buying another stock that has become cheap – thus not sitting idle in cash. That’s where good diversification and careful active portfolio management enters in (i.e., not falling off the horse in mid-ride). This, in short, is the game to be played: we want to ride only fresh horses, and then jump from a tiring horse to a fresh one, efficiently.

A Couple of Visuals

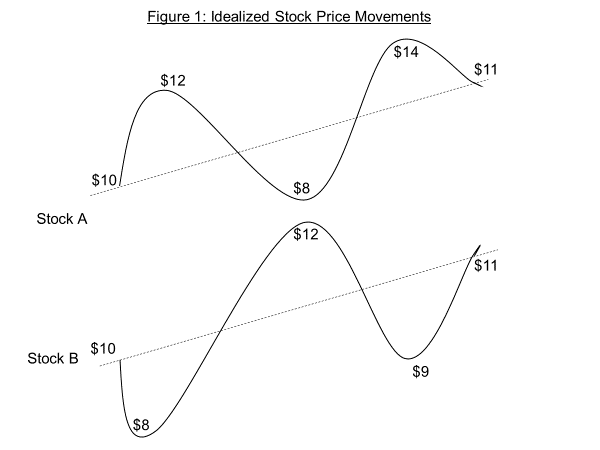

As Rod Stewart says, Every Picture Tells a Story, Don’t It. Figure 1 below tells our story. This is a highly idealized and indeed exaggerated situation, but it shows us what to look for. It shows us how volatility can be our friend. Imagine you are a buy-and-hold investor. You would be happy to own either stock A or stock B, as both are undervalued to the same degree. Both pay the same dividend. In one year, sure enough, you have a 10% price return from each. Add that to your dividend yield, and you’ve done well. Nothing to complain about. You’d be a hero in most institutional investment houses, or at least not a schmuck.

xxx

But imagine if you were an active trader under these circumstances. You would ‘know’ that stock A was not only undervalued, but also cheap (how we ‘know’ that is the subject of the technical analysis section later on). So, you would buy it, and not buy stock B (which you ‘know’ is locally rich). Local just means short term in this context – over the next few weeks or months. When stock A got close to its local price peak, you would sell it and look for something that is close to its local price bottom. Lo and behold, stock B is available and happens to be perfectly negatively correlated with stock A (this is idealized, after all). So we sell stock A for $12 and roll right into stock B at $8. We ride B up as A is coming down. Sure enough, we get to the point where B has become rich and A has become cheap, and so we swap horses again. We get to do this one more time before the year ends, when A has once more become rich and B has become cheap.

How much have we made for our trouble? $10 * 12/10* 12/8* 14/8 *11/9 = $38.4. This compares rather nicely to the $11 you’d have had with a buy-and-hold approach. Plus, we get all the cash from dividends that we would have gotten from a buy-and-hold approach, because we were never sitting idle in cash. Again, this is an idealized and exaggerated situation. In real life, we never see perfectly negative correlation, we’ll have some idle cash no matter how hard we try (indeed, there are times when having idle cash – dry powder – is exactly the right thing to do), and we almost never will nail the exact bottom or top of the sine wave.

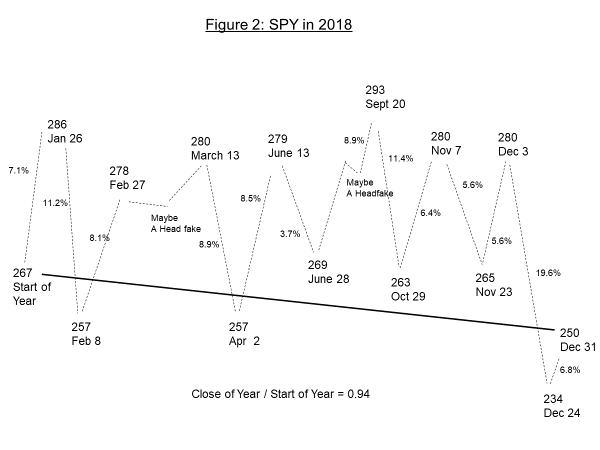

Just below is another example, a stylized price history of the SPY in 2018 – showing major peaks and troughs on the price chart. In a year that resulted in about a 6% price decrease from a SPY buy-and-hold strategy, there were multiple opportunities for returns from active management well in excess of 5%. Now on any given up-leg you won’t turn over all of your portfolio, but with 7 up legs of 5% or more, you would have done quite well if you’d paid attention to technical analysis. Most (though not all) of the peaks and troughs shown in Figure 2 were nicely captured by the MACD, a well-known technical indicator, on a daily timeframe – with relatively little ambiguity that a trend reversal was at hand. Given the ups and downs in the SPY in 2018, 2019, and 2020, does anyone really think it’s always a fairly priced measure of the US economy? It looks more like the output from a schizophrenic. We’ll discuss MACD in a little bit.

xxx

xxx

Technical Analysis, Patterns, Set Ups, and Entry Points

Now, we turn to technical analysis: assessing what’s cheap and what’s rich. The first essence of active management, where it begins, is getting a good entry point. There are a number of ways to do technical analysis, to try to get an edge on the entry point. And that’s what we’re seeking – an edge. You won’t get precision or omniscience. Some analysts use the Elliot Wave approach, others look for patterns in the candles (e.g., head and shoulders, bull pennant). Each method can add value when used by an experienced practitioner. Elliot Wave has the disadvantage that it’s complicated to do and requires considerable effort to maintain. Chart patterns have the disadvantage that there’s no quantitative component to the analysis – it’s entirely visual. Having said this, I am very mindful of resistance and support levels, and of stocks trading in channels. These are obvious ‘patterns’ that can be very meaningful indicators. FinViz provides charts on individual stocks, with their take on the trading pattern a given stock is in, and their free website is quite good. I used to think technical analysis was total B.S., but Wall Street uses it, so stock behavior is affected by it – whether I think it’s B.S. or not. It becomes a self-fulling prophecy if enough big money uses it. And since I’ve learned to make money using the technical analysis I describe below, I’m sold on its ability to add value. And that’s what all patriots want to do – add value.

We will explore here a middle ground approach involving technical indicators. These are algorithms that manipulate either the price data, the volume data, or both together. Through this mathematical manipulation, insight as to likely stock behavior is sought. Again, just a little edge. Technical indicators fall into three categories: trend, momentum, and volume. Hundreds of indicators (including variations on indicators) are available, though there are only a dozen or so major indicators that seem to come up all the time in discussions on this topic. I will not attempt a survey of the field here, but rather focus on what I use – after much experimentation with many of the others.

I don’t pay much attention to trading volume assessment, but when I do, I just use volume. There are all sorts of fancy ways to mathematically manipulate volume, but I like the simple, direct measure. It tells the story regarding supply and demand. The basic idea is that price increases or decreases on increased volume are more meaningful and likely to be sustained than such increases or decreases on lighter volume. No guarantees, just another clue. For a price-based indicator, I use MACD (which stands for moving average convergence-divergence). Through its very clever construction, it shows both trend and momentum. For me at least, it is a visually intuitive indicator that has been most helpful in assessing trend reversals – and that’s what you need to determine a good entry point, to buy something cheap or sell something rich.

In a nutshell, the MACD line is the difference between two EMAs (exponential moving average), usually selected to have periods of 12 and 26. On the weekly time frame, this gives measurement horizons of 3 months and 6 months. I use periods of 10 and 20 in trading to make the MACD just a bit more sensitive – but also subject to more false signals – there’s always a tradeoff. When the MACD is at the horizontal zero line (or equilibrium line), the two EMAs are crossing one another. When MACD is below the zero line, the shorter term EMA is below the longer term EMA. And vice versa. When the MACD is heading up, the short term EMA is either converging on the long term EMA (if below the zero line) or diverging from the long term EMA (if above the zero line). And vice versa. The steeper the slope of the MACD the faster the EMAs are converging or diverging (momentum). And vice versa. The best way to start getting familiarity with the MACD is to pull it up on a price chart (I use Trading View), and also pull up the two related EMAS. Watch how the shorter term EMA undulates (dances) around the longer term one. Watch what the MACD does, and watch what the price does.

There is also a so-called signal line associated with MACD, which is a shorter term SMA (simple moving average) of the MACD line itself – usually set at 9 periods. So it’s a smoothed MACD. Many analysts use the signal line as a, well, signal to buy or sell. A trend reversal signal. If the MACD crosses over the signal line from below, it’s a buy signal. If the MACD crosses over the signal line from above, that’s a sell signal. In practice, I have found that it’s usually better (though a bit riskier) to regard the bottoming or peaking of the MACD – which occurs before the signal line is crossed – as the buy or sell signal. When a bottom occurs, the shorter term EMA is beginning its turn up relative to the longer term EMA – though they both may still be going down. By the time the MACD line crosses the signal line, the fireworks are usually well underway. Usually bottoming and signal crossovers that occur below the zero line are more powerful than those occurring above the zero line – and the further below the zero line, the more power. The opposite is true for sell signals. In my trading system, the color of the MACD line changes from red to green when the buy signal is obtained (and vice versa).

MACD is thus a very visually intuitive display of trend reversals. But it also displays momentum. Typically, the difference between the MACD line and the signal line is shown as a histogram – in some trade systems these bars can be multi-colored to make the display of momentum changes even more visual. The bars are highest when the two lines are moving away from each other, indicating momentum is increasing. When momentum slows, the bars peak – then level off – just ahead of the bottoming or peaking of the MACD line itself. In my system, the cyan bars turn purple at the peak, and a couple of purple bars is a strong warning that momentum has slowed or stopped, and the trend may reverse. At the bottom, the bars turn from red to brown. There are other ways to use the MACD, and the interested reader is encouraged to survey the many web articles and YouTube videos on this topic and to experiment.

A few final thoughts on using the MACD. The longer time frames of daily and weekly tend to be relatively more reliable than shorter time frames. The weekly timeframe is a measure of a good long-term trend that can take a month or two to play out – you always prefer to swim with the current in the stream. I tend to trade on the 1 day MACD. But at any timeframe, MACD is a lagging indicator – not a leading indicator. I regard it more as suggestive than predictive. Prices drive the MACD, not vice versa. I patiently wait for the daily MACD to start bottoming (by which point the histogram has flattened and the bars are starting to decrease in height). I then wait for the 4-hour MACD to turn up – so everything is aligned. Then I start legging into a position. I don’t buy up to my position limit all at once, I leg in and see how it goes.

My Trading Set Up

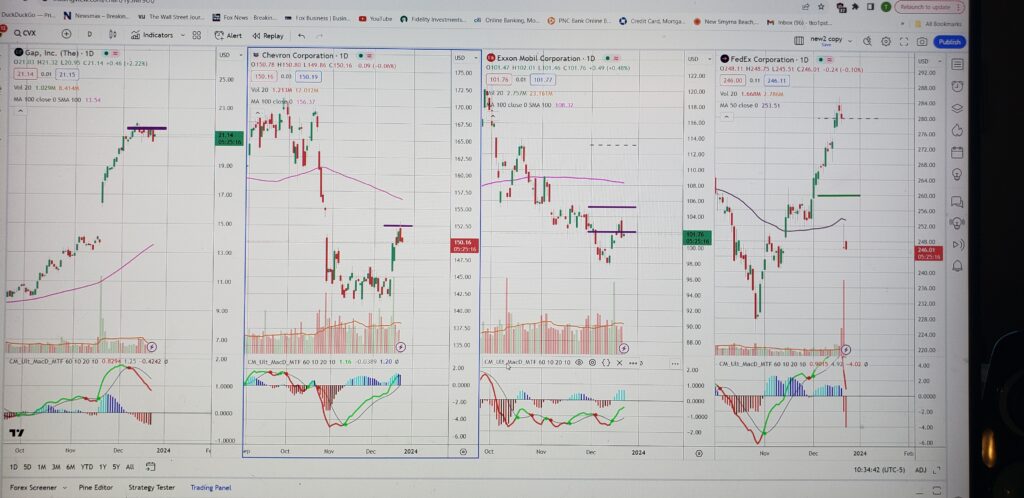

A picture is worth a thousand words, so here’s a shot of my trading screen.

Picture 1: Trading View Set Up (Chart by Trading View)

xxx

Let’s discuss my trading set up. Trading View plays a critical role in my trading. It’s a stock monitoring and display system, including charts and technical indicators. It’s a few hundred bucks a year, and it’s well worth the money. I could invest (though with more bad entries) without Trading View, but I couldn’t trade or engage in active management.

The first thing to mention is that I’ve got a nice big, high quality monitor (about 21” x 12”). This allows me to get multiple stocks on one page. I find 3 stocks per page is the best for my eyes, though four works too. The page I’m showing in picture 1 contains three stocks I trade, their price history on the daily time frame. It’s easy to get to a particular stock, and it’s easy to scan through the entire portfolio. For the particular version of MACD that I like to use (CM_Ult_MacD_MTF), when you access it from Trading View’s library of technical indicators, it shows up on a pane under the price trend for that stock (or ETF) with its default settings. These settings are fine, but you can adjust them as I do. And you can position panes differently if you wish. There’s a fantastic amount of customizability with Trading View. If you’re going to trade, I highly recommend this product. It has a little bit of a learning curve, because there’s so much capability, but it’s not too bad and it’s well worth coming up the learning curve.

So with this background, let’s take a look at a stock that seem to be cheap. You can see that FDX just took a major league dump, for whatever reason. It looks cheap. Time to load up or sell a put. On the other hand, GPS looks expensive. Time to sell it (take gains), or sell a call.

This leads me to the second essence of an active management approach is when to take gains (the first essence, of course, is getting a good entry). As we discussed in the previous section, the MACD indicator is used to determine the entry point. MACD can and should also be used to assist in determining the exit point (see picture 4 on the next page). Now you could just wait to exit until the MACD appears to be peaking on the daily or four-hour timeframe, with no predetermined gain hurdle – other than perhaps a minimum below which you won’t sell no matter what the MACD does. However, since all technical indicators are lagging, what can and will sometimes happen is that a seemingly smooth ride to the peak will suddenly be interrupted. You’ll get a discontinuity in the MACD wave. You’ll have a nice gain, you’ll be thinking it’s time to realize the gain, and all of a sudden, it’ll be down 4%. In a heartbeat. There go those hedge funds again. So much for efficient markets. And it may take a long time to recover or it might bottom and bounce right back. So, in practice I have found it helpful to use a deterministic hurdle applied to each individual stock to motivate taking gains – guided by what the MACD is telling me. That way I don’t wait too long to take at least some gains. This is always a battle of regrets: regret at having sold too soon and leaving money on the table versus regret at not selling when you could have, only to see those gains disappear. Neither is good, and where you set your return hurdle will in part be determined by your ‘regret utility function’. Yes, I made that term up. But that’s the idea – be clear on what you will regret more.

Here’s a simple deterministic rule I use: start pulling the trigger on sales when a given stock’s price appreciation approaches its yield. Sooner, if the market overall is toppy. Later, if the market has recently corrected and is starting a run up. The idea here is to follow the primary signal provided by each stock’s MACD and gain amount vs. yield, while keeping an eye on the overall market. Stocks can certainly go against the overall market trend, but you want to be aware of what that trend is. For dividend growth stocks, I watch the VTV ETF, as well as the QQQ and SPY (which is kind of an average of QQQ and VTV). By watching all three, I have a sense of how Wall Street is rotating out of one and into the other, or if they’re both crashing or both rising.

And notice I said start pulling the trigger; don’t sell the entire position as long as the MACD looks like it wants to go up. Try not to act precipitously. My thinking here is: if I can get a year’s worth of dividends (or even a half a year in toppy markets) from a quick sale, I at least start flipping it into something else that looks cheaper. This brings me to a very important point: to make this work, it’s necessary to have a good sized stable of stocks. The 40 stocks in my stable not only provide good diversification, as mentioned earlier, but when you’re actively trading, 40 provides lots of opportunity to flip stocks. It’s diversity of opportunity you’re seeking. They should all be stocks you’d be happy to hold long term. With a large stable, you increase your chances of being able to exit one stock and rapidly find another that’s out of phase (like Figure 1), thus avoiding being in cash too long. Of course, there are times when everything is crashing, and it’s best to just be in cash and not jump back into something else quite yet. Since your stable only has stocks that you’d be happy to hold long term, if you misjudge your entry, and it becomes even cheaper – you don’t mind it as much. You’ll still collect dividends on a solid company that you can expect will recover its price. You’ve become a buy-and-hold investor, at least for that stock. Lastly, I would note that one advantage of a rule that’s based on the yield of an individual stock is that the higher yielding stocks – that are harder to replace and that you’d really like to keep – tend to stick around longer than the lower yielding stocks that are easier to replace. Good stocks that are 3% yielders are easy to find; good stocks that are 5% yielders are very hard to find.

The trading options page shows how the MACD can be used to great effect, to trigger the sale of covered options. To learn how to model the option trading process, start at this page, and then go to parameter optimization and The Code.

Back to Home